Fascinante articulo sobre el incidente naval probablemente mas significativo durante la Revolución Mexicana. Esta es la versión ocular del oficial a cargo del destructor Americano USS Prindle, que solamente se limito a tomar datos sobre el encuentro.

THE CAREER OF THE MEXICAN GUNBOAT TAMPICO

By J. H. Klein, Jr.

The Mutiny

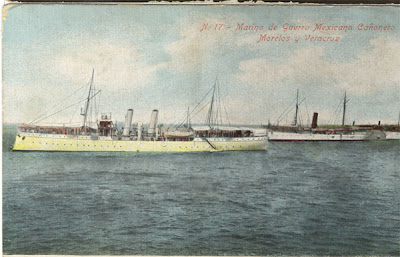

At the beginning of the year 1914 there were three Mexican gunboats on the west coast of Mexico, namely, the Guerrero, Morelos and Tampico, all under Federal control.

Buque de transporte Guerrero

Cañonero Tampico

Cañonero Morelos, al frente.

On February 22, 1914 (Sunday), at Guaymas, Mexico, about 8 PM, while about half the officers and men were ashore, the executive officer (Lieutenant Malpica), the paymaster (Rebatet), and two engineer officers (Johnson and Estrada) took charge of the crew of the Tampico, arrested the captain and the chief engineer, and announced that the Tampico would henceforth be under the control of the Constitutionalists, or the Rebels. The captain and the chief engineer were told that if they made no resistance they would not be harmed, and would, at the first opportunity, be turned over to the Federals. The mutiny, therefore, was accomplished without violence or bloodshed.

The Tampico immediately left Guaymas and stood to the northward intending to ram the Guerrero. Fortunately for the Guerrero, the Tampico's steering gear broke down and she then turned around to the southward and proceeded to Topolobampo, Sinaloa, arriving there on February 24. The captain and the chief engineer were then placed aboard the SS Herrerias, and sent to Mazatlan, which at that time was in Federal hands.

* Nothing has heretofore been written concerning the career of the Tampico except the official reports from vessels stationed on the western Mexican coast at that time. It was my intention at first to compile an official report of her operations, but the tale seemed so interesting that the "compilation" gradually became a "story." The official reports of Admiral T. B. Howard (commander-in-chief), Commander G. B. Bradshaw (commanding Yorktown), and Commander N. E. Irwin (commanding New Orleans) were consulted and the data derived there from were used in producing the following story which is of historical value because of its accuracy.

The exact cause of the mutiny is not known. Various vague stories have been circulated concerning the true reasons therefore, but no one seems to know which, if any, of these may be true. One story has it that the Federals owed the crew 4,000 pesos. Another story was told to the effect that Malpica had strutted the streets of Guaymas with a lady of questionable character (some say she was the captain's mistress) and as a punishment the captain sentenced Malpica to be reprimanded and to perform temporary duty with the army at the front. In order to avoid this sentence he was said to have hatched out the mutiny.

By common repute the Tampico had been a very "gay" ship in her day, and I was told that frequently week-end parties had taken place at which both sexes were present aboard ship for several days at a time.

Operations at Topolobampo

On March 2, 7:00 AM, the Guerrero, commanded by Capitan de Navio Torres, arrived off Topolobampo from Guaymas, and anchored outside the bar. At 10.30 AM the next day the Morelos arrived from Mazatlan, and anchored near the Guerrero.

At 9:37 AM, March 4, the Tampico was observed standing down from Topolobampo. The Guerrero immediately got under way and opened fire as she entered the channel. The Morelos got under way as soon as practicable and followed along astern of the Guerrero. As soon as the Tampico cleared Shell Point she returned the Guerrero's fire, whereupon the Guerrero stopped, backed out of the channel, and presented her broadside to the Tampico. At that time the Morelos was about 800 yards beyond the Guerrero away from the Tampico.

The firing continued until 10:05 AM during which time the Guerrero fired about 20 shells, the Morelos about six, and the Tampico 14, at a range of 8,000- 9,000 yards. The firing of the Guerrero and of the Morelos was very wild. Comparatively speaking, the Tampico fired fairly well. Of her shots one was spotted 50 yards short, one 50 yards over, and one slightly to the left.

At the conclusion of this brief engagement, the Tampico returned to Topolobampo and the Guerrero and the Morelos anchored outside, oft' the bar. No damage was done to any of the vessels. At that time the Tampico was said to have had about 70 tons of coal and about eight hundred 4-inch shells remaining on hand. At 8:40 PM the same day the Morelos left for Guaymas to coal and provision, returning to Topolobampo on March 9.

On March 13, at 8:50 AM, the Tampico again stood out; the Guerrero and Morelos getting under way as soon as possible. The Guerrero opened fire at 9 o'clock. As soon as the Tampico cleared Shell Point, she opened fire on the Morelos, her first shell landing about 20 yards short, range 9,000-10,000 yards. The Morelos returned the fire and began retreating to the southwestward, on which course she would have put the USS New Orleans in direct line of fire between herself and the Tampico. The Tampico then shifted her fire to the Guerrero and the Guerrero adopted the tactics of the Morelos. The New Orleans, of course, shifted berth as soon as possible.

All firing ceased at 9:12, the Guerrero having fired 13 shells, the Morelos nine, and the Tampico six, at a range of 9,000-10,000 yards, and no hits were made. It was again noted, however, that the gunnery of the Tampico was considerably better than that of either the Guerrero or the Morelos. The Tampico returned to Topolobampo while the Guerrero and Morelos anchored outside of the bar considerably to the southward of their previous anchorage. The Morelos left for Altata on March 30.

At 4:32 PM on March 31, the Tampico was again reported standing out. The commanding officer of the Guerrero, who was at that time returning an official call on the captain of the American cruiser, quickly returned to the Guerrero and got her under way immediately. The Guerrero took up a position off the channel broadside toward the Tampico.

About 5:30 PM, when the Tampico had reached a position abreast Shell Point, she opened fire on the Guerrero at a range of 9,000 yards, and was immediately answered. About 6 PM the Tampico headed straight for the Guerrero, going right on over the bar until she grounded below the entrance. By 6:15 she managed to get off the bar and headed northwest, straight for the Guerrero. The Guerrero retreated but continued firing.

At 6:30 the Tampico came about and headed back toward the harbor. Both vessels ceased firing at 6:40 because of darkness, the Guerrero anchoring off the bar while the Tampico proceeded on inside above Shell Point. During this engagement the Tampico fired both her 4-inch guns and one 6-pounder, while the Guerrero used her six 4-inch.

The firing on both sides was very wild. The range varied from 9000 to 2000 yards. The Tampico fired about 160 shells (4-inch and 6-pounder) and the Guerrero fired 162 4-inch shells, of which 20 were shrapnel and the rest armor-piercing. Malpica later on told one of our officers that the Tampico had been hit seven times during this fight, as follows: Two 4-inch shells passed through the officers' quarters under the poop, one 4-inch shell hit amidships near the water-line, four 4-inch shells entered the bow, one of which struck below the water-line and the other three hit near the water-line. There were no injuries to her personnel.

The hits were stated by Malpica to have been made during the period while the Tampico was swinging around on the bar. Later on it was discovered that the Tampico had sunk inside the channel above Shell Point.

The Guerrero was struck three times during this engagement; one 4-inch shell, armor-piercing, entered the star-board side of the berth-deck but did not explode, one 6-pounder landed on the skid frames amidships but did not explode, while another shell, either a 4-inch or a 6-pounder, cut a stanchion on the bridge. None of the crew on the Guerrero were killed, but a few suffered minor injuries.

On April 10 one of our officers inspected the Tampico and reported that she was aground, heading out, inside Shell Point on the south side of the channel with water covering her entire main-deck. The two 4-inch guns were still aboard as was one of the 6-pounders in the waist, all the other guns having been sent ashore for use with the army. She still had 600 rounds of 4-inch ammunition left, most of which was under water.

On April 2, during the forenoon, the Morelos returned from Altata. The Federal gunboats did not know, but they shrewdly suspected, that the Tampico was aground, so, in order to find out, the Morelos was sent in close to the bar. At a range of 8000 yards she fired 11 shells at the Tampico and the Tampico fired eight in return, with no damage on either side.

On April 9 an aeroplane came out of Topolobampo and dropped five bombs near the Guerrero and Morelos, one of which fell close to the Guerrero. Small-arms were used in an endeavor to drive off the aeroplane, but because of her height this fire was not effective.

Later on in the month the Federal gunboats, having discovered the true situation of the Tampico, withdrew to other ports. The Morelos, while in Mazatlan harbor, attempted to run well up into the inner harbor, and in doing so, ran high and dry aground. There she lay between the besieged Federals within the town and the Rebel besiegers around the outskirts until she was completely shot-up and destroyed by both sides. The Guerrero, in the meantime, steamed up and down the coast between Guaymas and Mazatlan wherever she was needed.

The officers of the Tampico were making every endeavor to raise the ship, and put her in serviceable condition. A diving suit was finally procured, the holes under water plugged up, and eventually the ship was raised.

Events Prior to the Final Battle

On June 11, 1914, the Tampico was reported as having been raised and made ready for sea. The commander-in-chief of the Pacific fleet (Admiral Thomas B. Howard, USN) was then off Mazatlan in his flagship California (now the San Diego). Several destroyers were kept with the flagship ready for dispatch duty. On Sunday, June 14, 1914, he received a report that the Tampico had that day sailed from Topolobampo.

Fortunately for me, my boat (the USS Preble DD12) was ready for a run, so I was detailed to find the Tampico at sea and then trail her. The Preble immediately got under way (about 3:30 PM) from Mazatlan, and started northward toward Topolobampo.

The destroyer Perry, then at La Paz, was ordered to head for Topolobampo and report by radio to the Preble for further instructions. As I did not know what course or speed the Tampico was making, I simply proceeded slowly (about 10 knots) overnight to Topolobampo in the hopes of sighting her about daylight the next morning. During the night I twice headed to the westward to investigate passing ships. This set me about 10 miles to the westward of my original course.

About 7:30 AM, June 15, another ship was sighted on the port beam (to westward), hull down, and masts hardly visible. This vessel finally proved to be the Tampico herself. Had I not been set to the westward in looking over the two steamers during the night I would not have had the good luck to find the Tampico so quickly. Her position then was Lat. 25° 14' north, and Long. 109° 01' west.

USS Preble

USS Perry

USS New Orleans

USS San Diego

I approached to within about two miles of her, and stopped. She also had stopped. As she did not get under way I approached to a position about a mile abeam of her in order to get a closer view, when I saw her lower a boat which headed toward the Preble. The officer in charge of the boat (Rebatet) came aboard, presented the compliments of his commanding officer, and told me the following tale; The Tampico had been under water about two months; she was raised, and thought to be ready for sea. On Sunday, June 14, she left Topolobampo under one boiler and proceeded to sea en route to Altata, Mexico.

There she expected to retube her boilers and improve the condition of her machinery, and then start out after the Guerrero. After destroying the Guerrero she would break up the commerce on the west coast of Mexico, and, by cutting off the supply of provisions at Guaymas and Mazatlan would cause these two main Federal strongholds to fall into Rebel hands. The Tampico had proceeded only about 30 miles to sea when her one remaining boiler had burned out and she was now temporarily helpless. He thought repairs could be made, and that by sunset the Tampico would again be on her way to Altata. Her complement at that time consisted of the officers mentioned above, the following three additional machinists (Filiberta Vela, Porfirio Gonzales and Floreus Araryo), and about 56 men.

After Rebatet had returned to his ship I withdrew to a position about two miles to the northwestward of the Tampico, hove-to to await further developments, and sent a radio code to the commander-in-chief informing him that I had found the Tampico. About 1 PM the destroyer Perry came in sight, received instructions, and also hove-to.

About 3 PM another boat put out from the Tampico and came to the Preble. The chief engineer (Johnson) and his senior assistant (Estrada) came aboard. They seemed to be in great distress and told me a tale as follows:

They could not repair their boilers; therefore they were at the mercy of the elements and would gradually drift ashore. They requested me to tow them to Altata — about 80 miles distant. (I declined on the grounds of strict neutrality.) They then begged me to send a radio to the American admiral, quoting their request. The captain of the Tampico had requested that I come aboard to see him.

I sent the radio to the commander-in-chief as they requested. When I showed them the rough draft of the message in radio-code they were very pleased because they had feared that I might send the message in plain English and that the Guerrero would pick it up and discover how helpless they were. And as they could not understand the message, they were certain that the Guerrero could not.

About 5:30 PM I boarded the Tampico. Captain Malpica excused himself for not having called, pointing to the bandages on his left foot. It seemed that about two weeks previously he had accidentally discharged his revolver into his foot, and as a result he could barely hobble about. During my conversation with him I gained a very favorable impression of his ability and determination. He spoke a little English, and, with my poor scraps of Spanish, we managed to piece out a very fair conversation. He seemed very grateful for my having forwarded his request for a tow to the commander-in-chief, and was anxious for me to inspect his ship thoroughly, to see for myself in what a pitiful condition she was. Accompanied by the executive and the chief engineer, I inspected the ship from truck to keel.

I was most anxious to see her, but as the inspection progressed I became more and more depressed. It was impossible to see such a helpless vessel, completely at the mercy of the wind and sea, totally unfit to steam or remain afloat, much less to commence the unequal struggle with the Guerrero which was imminent and inevitable, without a feeling of pity for these poor fellows. Above all, I could not suppress a feeling of admiration for this brave man, which increased at the end of the inspection, when upon asking Malpica what he would do if the Guerrero appeared, he defiantly answered: "I'll fight her and sink her if she will only come within range of my guns." These words could only come from either a fanatic or a remarkably determined man.

Conditions aboard that ship cannot be properly expressed in words. The captain's cabin was littered with boxes of stores, provisions and small-arm ammunition. These cases looked as if they had been thrown aboard from a great height and then left scattered, bulged and broken as they fell. The furniture was dilapidated and musty. A steel safe and two magnificent brass candelabra stood among the broken cases. A large quantity of alcohol was said to have been stowed beneath the captain's cabin. The officers' quarters were in the same sad condition.

Out on the main-deck was strewn every imaginable variety of splinter-producing litter. Broken cases, bales of hay, ammunition boxes, and Lord only knows what not scattered all about. Among it all, three cows sauntered aimlessly around assisting in messing up the decks.

Four 6-pounder semi-automatic guns had originally been installed in the waist. All these guns were now missing, and only the broken pedestals remained.

On the skid-beams overhead were the pulling boats which were a long way from being seaworthy or clean. The radio shack, a wooden house about 5' by 5' by 8', was also mounted overhead between the boats. The ship carried an aerial, but there were no radio instruments aboard. Had a shell exploded among these boats the fragments and splinters would have killed or injured every one on the main-deck. The bridge was a small, rickety affair. On the port side a small machine gun had been temporarily mounted. About 30 boxes containing the loaded belts for this gun were piled about on the bridge.

The Tampico had a raised deck forward and aft, on each of which was mounted a 4-inch rapid-fire gun. The officers said that these guns were unreliable, and that they expected trouble with them. A casual examination showed that the breech blocks were loose on their hinges, the rifling badly eroded, and that there was much lost motion in the training and elevating gear. The sights were of a very antique design. Not only did they have much lost motion, but the cross-wires in the rear sight could not be brought to coincide with the front sighting notch. In my opinion these guns were more dangerous to their own crews than to the enemy.

Ammunition was scattered all about the forecastle and poop. Some of the shells were lying out exposed to the weather and some were still in their boxes. Shrapnel, blind shell, and armor-piercing shell were mixed promiscuously, although there seemed to be more shrapnel than any of the other. As this ammunition had been under water for two months I had grave doubts as to whether it could be fired at all, much less with any degree of accuracy. I was told that they had but 100 rounds of 4-inch shell of all kinds in the entire ship. Inside the forecastle on the main-deck level were two 6-pounder semi-automatic guns. These seemed to be in fair condition and had an unlimited supply of ammunition. (Only one of these guns could be used in the battle next day as the Guerrero did not steam over on the port side of the Tampico.)

Below decks the same disorder and dirt was in evidence. Broken wooden fittings were piled up in all corners, a fine opportunity for fire in action. The old shot holes which had been received in previous engagements were plugged up with makeshift leak-stoppers. The officers stated, however, that she was dry and water-tight.

The engine-room was indeed a sorry spectacle. Everything seemed to be rusty and out of commission. The main engines themselves were rusty and filthy, but they had succeeded in going about 30 miles with them at very slow speed. The generator was hopelessly ruined by the salt water, so they had neither electric power nor lights, except kerosene lanterns. Several pumps were said to be in fair condition. The ice-machine was not working, but of that they had little concern at this time. The evaporator, they said, could be used if they could only get steam from the boilers.

The two Babcock and Wilcox boilers were dead, the fronts of the casings were off, hand-hole plates removed, and many tubes exposed to view. Salt crystals hung from the tubes, the steam piping, the fresh-water piping, and gauge glasses. According to the chief engineer about 500 tubes needed plugging. They were using wooden table legs to make these plugs. Several firemen while hoisting ashes were singing away as if they were really happy.

The executive told me that the engineer officers had been in the fire-rooms constantly to tend the steaming boiler, but that during the temporary absence of one of them, the inexperienced firemen had carelessly ruined the boiler. This defection on the part of the engineers was evidently one of the bones of contention aboard the ship, and caused the reprimand of which I shall tell later.

The executive said that the engineers' force was composed of five engineer officers and 15 "shovelers" (as he expressed it). It seems that they had no artificers, machinists'-mates, oilers, or water-tenders, and that the "shovelers" were very inexperienced.

The crew were a hard-looking lot of Mexicans. They seemed to be but poorly disciplined, if at all, as during the inspection they swarmed about and would not give gangway to the officers until spoken to very sharply. One of them in fact lolled in a broken-down armchair on the starboard side of the quarterdeck, smoking a cigarette in a most nonchalant manner. Many of the crew wore bandages — evidences of previous engagements. They were poorly clothed, some of them wearing hardly any clothes at all.

Inquiries among the various officers as to the number of men in the crew brought answers ranging from 38 to 56. It seems none of them knew exactly how many men were aboard. By checking up the prisoners and wounded I estimated that the crew consisted of:

- 1 commanding officer,

- 1 executive officer,

- 1 chief engineer,

- 1 assistant engineer,

- 3 machinists,

- 15 in engineers' force,

- 14 in seaman branch,

- 25 soldiers.

- 61 total.

After finishing the inspection, I had another conversation with the captain in his cabin. He seemed anxious for a reply to my radio in regard to towing him to Altata, and was disappointed when I told him that I hardly expected one before daylight. Before I left he insisted that I have a drink with him of the vilest liquor I have ever tasted. He seemed loath to have me go, and made me promise that I would come aboard at noon the next day to sample a cocktail for which he claimed exceptional virtues. (The poor man had crossed the line by noon the next day.) I inquired about his supply of food and water and he told me that he could hold out for at least two weeks.

During the night all the vessels drifted in various directions. The Perry and Preble took position to the westward of the Tampico so that in case of any grounding the Tampico would ground first and give us a chance to clear out.

About 10 PM we sighted a vessel approaching from the southward. She steamed to within two miles of us and then sheered off to the westward. She was probably some coastwise trading vessel, but of this I am not positive. The three ships must have presented a very queer appearance.

The Tampico was burning several dim oil lamps which could hardly be made out at a distance of one mile. The Perry and Preble had their running lights on and also the white masthead lights. In addition, being under way, but stopped, we laid our red speed-indicator lights on the foremasts burning. A merchantman on coming upon such a combination of lights in a ]ilace usvially and supposedly clear of all ships, lights, etc., must certainly have been surprised, and I cannot blame her for making a sudden change of course to westward in order to give us a wide berth.

During the night we intercepted a radio from the New Orleans (then south of Guaymas) to the commander-in-chief, stating that the New Orleans was trailing the Guerrero on a southerly course. From her 8 PM position I figured that the New Orleans and the Guerrero would pass us about 7 AM the next day. To my mind that information sealed the Tampico's fate. We, on the Preble, discussed the impending battle, and I am sure none of us slept very soundly during the night. It was a very peculiar feeling to know that the Guerrero was bearing down on the helpless Tampico, and yet we were unable to inform the Tampico of the surprise in store for her. However, my orders were to watch and wait and to report everything, but to assist neither side.

Some time during the night the Tampico drifted over a 22- fathom shoal and dropped both her anchors. Her position on anchoring was Lat. 25° 28' 30" North, Long. 109° 18' West, and it was there in that position that she was sunk.

About daylight the next morning, June 16, we sighted two vessels to the northward bearing down on us very rapidly. About 5:30 they were recognized as the Guerrero and the USS New Orleans (Commander Noble E. Irwin, USN, commanding). The Guerrero stopped and cleared for action, and about 7 AM stood down toward the Tampico to commence the fight.

The Tampico hoisted her flag to the gafif — evidently the only preparation they made for action. This flag was an enormous Mexican national ensign, and all out of proportion to the size of the ship. And then commenced the action between the two ships, each flying the same national colors.

The position of the combatants and spectators at about 7:45 AM is shown on the accompanying sketch. The officers and crews of our vessels were very excited, the men swarming all over the topsides and rigging, armed with cameras and binoculars. The majority were in deep sympathy with the Tampico, not because they had any real preference for that vessel against the Guerrero, but because all humanity unconsciously sympathizes with the "under dog." During the action whenever the shells from the Tampico landed near the Guerrero, our men cheered, and, conversely, groans were heard when the Tampico was hit.

The flow of "sailor-man's repartee" was particularly strong, especially when the men criticized the poor gunnery of each side. After the vessels had been "expending ammunition" for an hour or more with little result, the seriousness of the encounter was lost, and much foolish comment was heard. Shells falling beyond the target were called "home runs" while those striking closer were called "triples," etc.

On one occasion, when one of the Tampico's shells fell about one-third of the way to the Guerrero, the helmsman leaned over to the quartermaster and said. "Gee, that wasn't even a respectable bunt," to which the quartermaster replied, "Those boobs on the Tampico will starve to death before the Guerrero hits her." During the battle the Preble ran back and forth midway between the two firing ships, at right angles to the line of fire, and about two miles clear.

Whenever the Guerrero came about we did likewise, following each of her movements, but being from one to two miles south of her, we interfered in no way.

The weather was ideal, clear and warm, with just sufficient breeze to blow the smoke clear of the guns. The sea was almost dead calm.

PLAN OF BATTLE OFF TOPOLOBAMPO, MEXICO

June 16, 1914

In order that my impressions of the battle would not later on become confused, I had a yeoman stand near me with a stopwatch, pad and pencil and jot down all the steps of the engagement (I dictated to him as they occurred), noting the time of each event. In this way "imagination" was eliminated.

The Final Battle

True to his word, Malpica was the first to begin the engagement, firing his after 4-inch gun at 7.47 a. m. (Mazatlan time) at a range of about 8,000 yards. This shell fell 400 yards short. The Guerrero promptly answered with one gun, the shell falling 1,000 yards over. By 7:50 the engagement had become general. The Guerrero was using all of her 4-inch guns, while the Tampico could use only her two 4-inch and the starboard 6-pounder. Whether the Tampico ever fired her machine gun or not is questionable, as the range was never reduced sufficiently to enable the machine gun to reach the Guerrero. The firing on both sides was very erratic. There seemed to be no attempt made at spotting.

At 7:51 the range was reduced slightly and the Guerrero changed course to starboard, i.e., away from the enemy. At 8:02 the Guerrero stopped temporarily, the starboard battery presented to the Tampico, range estimated about 6,000 yards. Between then and 8:11 the firing was very poor. Neither ship had as yet made any hits. Some of the Tampico's shells were falling about half way to the Guerrero, this no doubt being due either to the defective, wet ammunition or to the failure of the elevating gear. (See story of men, noted near the end of paper.)

At 8:13 both vessels ceased firing for three full minutes, and then the Tampico opened again. It was at this time that we noted the manner in which the Tampico's guns were being served. It seemed to us that the gun's crew would load the gun and lay it in the general direction of the enemy. Then the men would back away from the gun and lie down flat on deck while some one pulled the firing lanyard. I do not believe that any attempt was made to keep the guns continuously on the target while firing. One officer on the Preble stated that he had observed the same procedure on the Guerrero, but I saw at various times the pointer at the gun when the Guerrero's guns were fired.

At 8:20 the Guerrero came about, presenting her port broadside to the enemy. Firing was speeded up, but all shells were falling short. Evidently when they changed course away from the enemy, thereby increasing the range, they failed to change the setting of the sights.

About 8:22 the Guerrero began easing toward the Tampico very slowly and at 8:24 made her first hit — after 30 minutes of firing. This shell struck the main-deck between the mainmast and the poop. A large cloud of white smoke arose, but no damage seemed to have been inflicted, and, as there were no guns in that part of the ship, the Tampico did not suffer any reduction of gunfire thereby. This shell was evidently shrapnel. (Later on I was told that the Guerrero had fired practically all shrapnel throughout the engagement.) Firing continued as before, i.e., very slow, and correspondingly ineffective.

Before the fight the Tampico had lowered all her boats and had secured them to her port lower boom on the unengaged side. At 8:34 one of these boats got adrift and floated clear of the ship.

At 8:35 the Guerrero had advanced to a range of about 4000 yards and then changed course to port, i.e., away from the Tampico. This period marks the least range of the entire two hours of fighting. It is probable that at this stage the Guerrero was struck. We discovered later that she had been hit twice during the engagement, but as neither hit did any damage we did not know at exactly what time they were made.

The Guerrero came about at 8:40 and headed for the Tampico again, and at 8:48, after one hour of fighting, she scored her second hit. This shell carried away the Tampico's gafif and with it went the immense flag previously mentioned. No physical or material damage resulted, but the loss of the Tampico's colors no doubt cheered up the Guerrero's crew. Two minutes later, at 8:50, the Guerrero came about and headed away from the enemy.

During the entire engagement the Tampico was at anchor. She however resorted to a ruse which may or may not have gained its end. Oily waste and other combustibles were burned in the smoke pipe in the attempt to lead the Guerrero into thinking that the Tampico was actually under way. This could hardly have deceived any one, but it does seem odd that the Guerrero failed to steam across the Tampico's stern in order to gain a greater danger space for her guns and to reduce the effective fire of the Tampico to the lone 4-inch gun mounted on her poop.

The Guerrero came about and presented her port side to the enemy at 8:52, at an estimated range of 5,000 yards. I noted the firing interval at this stage and found that the Guerrero was firing at the rate of two shots per minute (six guns) and the Tampico at the rate of one shot every two minutes (three guns). No doubt the Tampico's defective ammunition did not fit in the guns, necessitating a waste of a great deal of time in trying to select brass cartridge cases that would go all the way into the chamber and permit the breech block to be closed. Furthermore, as they originally had only about 100 rounds of 4-inch, they may have been trying to save their supply until the Guerrero should reduce the range.

Two more of the Tampico's boats got adrift at 9:01. The Guerrero, at 9:07, probably angered by the long-drawn-out proceeding, headed for the Tampico and began to fire salvos. The mean point of impact was "The Gulf of Lower California" with the distance from the target expressed in "miles" instead of in "yards."

One salvo was spotted as 500 yards over, 1,000 yards over, and 2,000 yards over, and this was a representative salvo. None of the salvos straddled the enemy. This erratic firing provoked much mirth among the Preble crew and there were many cries to the Tampico to "Soak her now!" The Guerrero, still heading for the Tampico, slowed down at 9:14 until she barely had steerage way on, and at 9:17 she turned away to port.

After the engagement I discovered that the Tampico had been hit in the starboard bow close to the 6-pounder gun, and that the shell had exploded inside the forecastle. That hit must have been made at about this period, but we could not see it from our ship. The forward 4-inch gun did not fire after this, and it is very probable that the exploding shell crippled that gun, possibly destroying its foundations. At 9:18 a shrapnel exploded just short of the Tampico, midway between the smoke pipe and the forward bridge. This shell did not seem to hurt the ship itself, but the fragments probably killed some of the crew.

At 9:20 flames and smoke were seen to spring from the Tampico's quarterdeck. How they attempted to put this fire out I do not know as they had no steam on the ship and consequently would have no pressure in their fire-mains. Incidentally, the alcohol stored beneath the captain's cabin must have given them cause for anxiety.

At 9:42 the Tampico's gasoline-launch and one pulling-boat came around her bow and secured along her starboard (engaged) side amidships. These boats remained there but a minute and then returned to the port side. Preparations for abandoning ship were evidently in progress.

At 9:45 the flames on the Tampico's quarterdeck flared up with renewed vigor. Smoke poured forth in large volumes and completely enveloped the after gun. In spite of this the Rebels fired two more shots from that gun, even though I could not see the gun through the smoke and flames. One of the gun's crew stood up on the burning poop and defiantly waved a large flag. The Guerrero continued firing until 9:50.

It was then that we saw the Tampico's crew in their boats, the gasoline-launch towing one pulling-boat, heading for the shore. After the ship had been abandoned, the Guerrero ceased firing and proceeded at full speed for these boats in order to intercept them before they could get into shoal water. The battle proper ends at this time — 9:50.

Events Immediately After the Battle

After a chase of about half an hour the Guerrero caught up with the two boat-loads of the Tampico's men. As there was no further hope for the boats to escape they pulled along side of the Guerrero and the prisoners were taken aboard. While the prisoners were climbing up the Guerrero's ladder, Malpica, standing up in his boat, in plain sight of everybody on the Guerrero, calmly placed his revolver to his head and shot himself, dying almost instantly. The Guerrero half-masted colors immediately, all the American vessels following suit.

The commander of the Guerrero sent a radio to the commander of the New Orleans thanking the American vessels for half-masting colors "in honor of the death of Malpica." The Guerrero returned to a position about 400 yards to the southward of the Tampico and anchored. Boats were sent out from the Guerrero to the Tampico to investigate conditions aboard the latter ship, and a tow-line was passed from the Guerrero's stern to the Tampico's bow. The rescue party, however, reported that the Tampico could not be saved, and later on the tow-line was cut.

When the Guerrero ceased firing and started in pursuit of the boats, the American vessels closed-in on the Tampico, in order to render such assistance as might be needed; the Preble, happening to be the closest at that time, was the first to reach the spot and steamed to within 50 yards of her bow.

There were several men rushing about her forecastle waving white rags. They climbed down the port boom and down the anchor cable, but refused to slide into the water and swim to the Preble. In the meantime the fire was spreading and the fixed ammunition was going off in all directions. Small-arm ammunition cracking away sounded like a machine gun. Suddenly the after magazine blew up and 4-inch shells were sent in all directions. Several of these were plainly seen and heard as they flew through the upper rigging of the Preble.

At this juncture the New Orleans appeared and took charge of the situation. She lowered two boats which went close under the Tampico's bow and rescued the men who were jumping into the water close to the boats. Later on the Guerrero's boats picked up the last man who was floating about on a plank after the ship had sunk. That was Rebatet, the ex-paymaster, severely wounded.

While the Preble was close aboard the Tampico I noted the following conditions:

- The main-deck aft had caved-in and the stern of the ship was a seething cauldron.

- The starboard side of the forward bridge was wrecked.

- Two corpses were plainly visible on the port side under the bridge.

- The main-deck was covered with splintered gear fore and aft.

- Shrouds of the mainmast were hanging over the stern.

- The foretopmast was pierced, but the stick was still standing.

- Gaff and colors were shot away.

- Part of the aerial was carried away.

- The after 4-inch gun had fallen down into the fiery furnace.

- Rolls of paint were hanging from the outer shell aft clear down to the water-line.

The Tampico gradually listed to starboard, as the water came up higher and higher. At 11:35 the water had reached the main deck and began to flow aft until finally it had risen sufficiently high to flow over the hatch coatings and down into the hole in the stern.

At 11:57 clouds of steam arose, showing that the water was now flowing into the hole and the end was near. She heeled to starboard sharply, and, at ii.S7i, her stern sank very suddenly lifting her bow up to an angle of about 45°. There she held for an instant, the imprisoned air in her bow buoying her up. The air-pressure now began to rip up the planking in the main-deck and spouts of water spurted up as the seams parted. The bow came up vertically, and then, with very little commotion, the ship slid down stern foremost under the surface. There were very few bubbles and no suction. All that remained of the Tampico were a few bits of floating wreckage. She sank in 22 fathoms.

About 1 PM Captain Irwin called on the commanding officer of the Guerrero and took me along with him. We met the captain and the executive officer, and had a short talk with them. They showed us the two holes in the Guerrero, which had done no damage to either the ship or personnel. There was no gayety or any feeling of exultation aboard that ship; on the contrary, a funereal air seemed to pervade everybody and everything.

They were very sorry that this battle had had to be fought, and especially regretted the death of Malpica. As they said, Malpica had been respected and admired by all the officers of the Guerrero, many of whom had previously served with him. They were profuse in their praises of his courage and ability and mourned his loss as that of a true friend instead of a defeated enemy.

The injured aboard the Guerrero were being- attended by Surgeon McLean, USN, of the New Orleans, assisted by the medical officer of the Guerrero.

The captain of the Guerrero stated that the prisoners would be treated kindly and I doubted very much if he would turn them over to the Federal authorities when he reached Mazatlan.

Review of the Battle

The Guerrero used six 4-inch guns throughout the battle, and fired practically nothing but shrapnel. We were told that she was endeavoring to fire high in order to kill off the personnel and force a surrender rather than to injure the ship. The Tampico used her two 4-inch guns and her starboard 6-pounder, firing common, armor-piercing and shrapnel indiscriminately. The Guerrero fired 263 rounds and the Tampico 75. The Guerrero was struck twice, as previously noted. Her personnel escaped injury.

The New Orleans took six men off: the Tampico, of which two were wounded; one of these died the following day, the other five were taken aboard the New Orleans to Mazatlan and, as I understand, eventually transported to the United States. The captain of the Guerrero did not request the surrender of these men from the New Orleans to the Guerrero. Of these six men one was a seaman (second-class), two were petty officers (second-class), and three were privates of infantry (soldados).

The captain of the Guerrero stated that of the men taken prisoners from the Tampico 12 were seriously wounded, and 12 to 15 more suffered minor wounds.

Later on I interviewed these prisoners aboard the New Orleans. The two petty officers (Francisco Alvarez, BM, 2nd class; and Aciano Lamos, BM, 2nd Class), agreed in their tales, the substance of which is quoted :

Captain Malpica took charge of the after 4-inch gun. The executive (Rebatet) similarly took charge of the forward 4-inch gun. The chief engineer (Johnson) was on the bridge with the machine gun. Throughout the fight the soldiers were a source of considerable trouble, as they did not know the ship and the guns, and had no taste for fighting aboard ship. They were the first to abandon the vessel.

The Tampico was hit above water five times:

(a) One shell killed two men, Luesa and Salvador.

(b) Another hit did no damage except to carry away the colors.

(c) The third hit killed one soldado, and proba1ly was the shell that wounded Rebatet.

(d) The fourth hit killed two men, and seriously wounded Estrada. During the engagement Malpica had rebuked Estrada for carelessness in allowing the boiler to be burned out, telling him that he was the direct cause for the condition in which they now found themselves. Estrada, wounded, went into the radio shack and, with his head between his arms, cried over his reprimand, and died in that position. It was also reported that he had shot himself while in the radio shack. His body sank with the ship.

(e) The fifth hit did no damage.

In addition to these hits, these men claimed there were seven hits in her stern under water. I do not believe it possible that seven shells could have struck there without our seeing some of them as they struck. These shells were said to have exploded in the ship, setting fire to the alcohol and thereby starting the fire which finally caused her to sink.

When the ship was abandoned Malpica was the last to enter the boats. These men and the other men who had been rescued by the New Orleans had gone below to plug up shot-holes under water. They had been called to come on deck to abandon ship, but they thought there was no special hurry and delayed, and when they did finally come on deck the boats had shoved off. They did not blame Malpica, but took all the blame on themselves for having been abandoned aboard ship.

The elevating gear on the after gun had broken down during the action. The forward 4-inch gun was disabled soon after the firing started. They had fired all their ammunition that was fit for firing before they left the ship and then abandoned because the fire could not be checked and the water was rising in the hold. Before abandoning her, the crew opened the sea-valves. To the best of their knowledge, there were only five men (all dead) aboard ship when she sank.

To sum up the fate of the officers and men: Malpica (commanding) committed suicide. Rebatet (executive) wounded in chest and leg; found floating on plank; was cared for on Guerrero, and probably survived. Johnson (chief engineer) prisoner on the Guerrero, uninjured. Estrada (assistant engineer) died in the radio shack and body sank with the ship. Vela, machinist 1 rate unknown; probably prisoners on Gonzales. Guerrero. Araryo, J

Of the crew, six were prisoners on the New Orleans, of whom one died. There were about 48 prisoners on the Guerrero, of whom 12 were seriously injured and 12 suffered minor injuries. The remainder, about five, were undoubtedly lost with the ship.

Tomado de: Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute, United States Naval Institute Vol 44, Annapolis, Md. : U.S. Naval Institute, 1918

http://www.archive.org/details/proceedingsunit30instgoog Accessed 10/11/2009

http://books.google.com/books?id=9EFQVPPJw9AC&oe=UTF-8 Accessed 10/11/2009

1 comentario:

Felicidades por el articulo de referencia, es muy importante recordar este tipo de hechos historicos, los cuales cada día son menos, la hiostoria pasa a segundo termino en la actualidad y no hay que dejarla morir

Saludos Andres Huerta Mejia

Publicar un comentario